Authors: Eric S. Mull, DOab, Rachel Gaudio, DOab, Brent Adler, MDc, Sergio A. Carrillo, MDd, Jonathan R. Honegger, MDeb, Rachel Supinger MS, LGCf, Nicoleta C. Arva, MD, PhDg, Miriam Conces, MDg, Melanie Babcock, PhDbgi, Nathan Fagan, MDh, Grace R. Paul, MDab

aDivision of Pulmonary Medicine; bDepartment of Pediatrics; cDepartment of Radiology; dDepartment of Cardiothoracic Surgery; eDivision of Infectious Diseases; fDivision of Pediatric Genetics; gDepartment of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine; hDepartment of Interventional Radiology; iThe Steve and Cindy Rasmussen Institute for Genomic Medicine, Nationwide Children's Hospital

Case

A previously healthy 8-year-old male presented to his primary care provider (PCP) with a 1-month history of cough and intermittent low-grade fevers ranging from 100.4–101°F. The cough was described as dry and had been improving since his initial visit. His fevers began around the time the family moved into a new home where mold exposure was detected. On physical examination, no focal findings were noted.

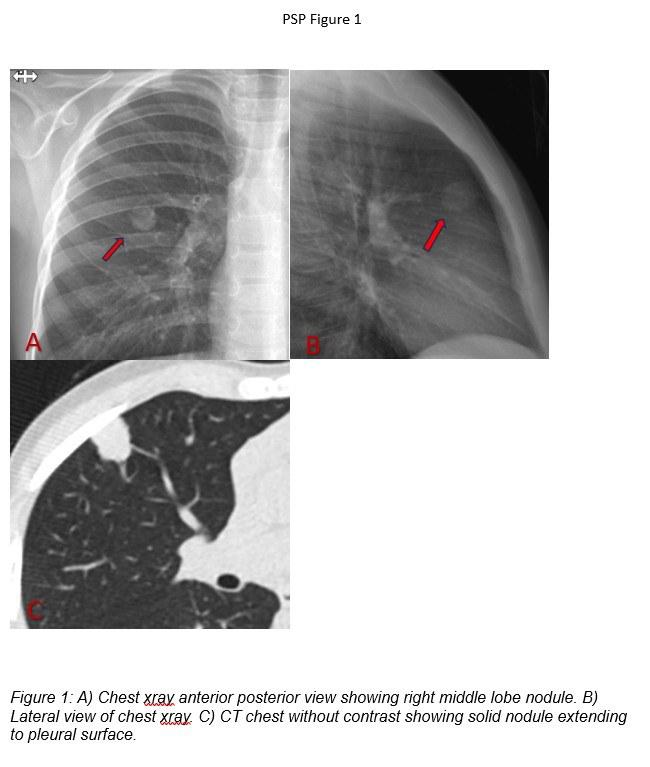

A viral respiratory panel detected rhinovirus/enterovirus. A chest X-ray revealed a right lung nodule measuring 1.3 × 1.4 cm without calcification, with otherwise normal lung fields (Figure 1A-B). Chest computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast redemonstrated the right upper lobe nodule, now described as a lobulated solid lesion without calcification or fat, extending from the parenchyma to the pleural surface and measuring 1.5 × 1.6 × 1.2 cm (Figure 1C). No lymphadenopathy was observed.

The patient was referred to infectious disease, where he underwent a comprehensive workup. Evaluation included inflammatory markers, CBC, fungal antibody panel (histoplasma, blastomycoses, aspergillus, and coccidioides by complement fixation and immunodiffusion), histoplasma IgM/IgG EIA, histoplasma antigen (blood and urine), tuberculosis interferon gamma release assay, cat scratch disease antibodies, uric acid, and lactate dehydrogenase. Results were all within normal limits, except for an intermediate histoplasmosis EIA IgM. Repeat testing three weeks later was negative for histoplasma IgM EIA and remained negative for histoplasma antibody by IgG EIA.

Correct!

Discussion

This 8-year-old patient presents with a persistent pulmonary nodule in the setting of a prolonged dry cough and low-grade fevers, with initial infectious workup largely negative, except for a transiently positive histoplasma IgM. The nodule is solid, lobulated, non-calcified, and extends to the pleural surface, which raises concern for infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic etiologies. Given the size of the nodule is greater than 8 mm in size, further evaluation is warranted to establish the final diagnosis.

The patient underwent transthoracic CT-guided needle biopsy and histologic findings were consistent with pulmonary sclerosing pneumocytoma (PSP).

Flexible bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) may aid in evaluating for an infectious etiology; however, due to the location of the mass, accurately targeting the desired area for saline instillation may be challenging. Positron emission tomography (PET) employs a radiolabeled tracer that accumulates in cells with increased metabolic activity (e.g., malignant cells, inflamed tissue, active neurons). While PET imaging can provide supportive diagnostic information when interpreted alongside clinical findings, it lacks the specificity to establish a definitive diagnosis.

Having the patient undergoing a VATS wedge resection would certainly provide a diagnosis, it can be associated with serious complications and is not the best first line therapy the location of this nodule. While transthoracic CT-guided needle biopsy carries a risk of pneumothorax in pediatric patients, it is more likely to be successful with peripheral lesions, it can provide tissue for histopathologic diagnosis. Histologic findings were consistent with pulmonary sclerosing pneumocytoma (PSP). Pathologic analysis revealed a lesion with small spaces lined by cuboidal cells with hyperchromatic, hobnail nuclei resembling pneumocytes, containing focal papillary structures. The stroma was focally fibrotic and, in some areas, round to oval larger, paler cells were found. Both cell populations appeared positive for Thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and Epithelial Membrane Antigen (EMA) staining (Figure 1E-F), which are stains specific to detect lung epithelial cells.

Previously known as pulmonary sclerosing hemangioma, PSP was first described in 1956 by Liebow and Hubbell1, due to belief that these tumors were sclerosing variants of hemangiomas2. However, recent immunohistochemical studies strongly suggest they originate from respiratory epithelium, particularly type II pneumocytes. Most recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified these as adenomas/epithelial tumors1.

This condition is typically diagnosed in the fifth decade of life with a high female predominance (female:male ratio of 5:1) and more commonly found in the Asian population. Most patients are asymptomatic (50-70%) with tumors incidentally detected on chest imaging1. However, when symptoms are present, they present commonly with hemoptysis, cough, or chest pain1,3. Despite the common prevalence in middle-aged individuals, there are reports of occurrence in children as young as 1 years old3.

PSP is often described as a solitary, peripheral, well-defined, homogenous nodule with rare cases of bilateral presentation. There are no pathognomonic radiological characteristics for PSP. On gross examination, lesions appear as well-circumscribed, firm tan masses that usually measure 0.3-7 cm in size with focal areas of hemorrhage, usually located close to the pleural surface1. PSP is histologically characterized by the presence of two cell types: cuboidal surface epithelial cells and round stomal cells. The surface cells resemble type 2 pneumatocytes2,4 and both cell populations have identical immunophenotypes with expression of Thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and Epithelial Membrane Antigen (EMA).

Though PSP is a rare benign neoplasm, it does have a rare potential to metastasize to the lymph nodes, especially to mediastinal and hilar nodes. One case series suggested that tumors in younger male patients are more likely to metastasize5. However, hematogenous spread has not been detected in patients to date. Given the risk of metastasis, limited resection is highly recommended, which is curative without the need for adjunctive therapies1. The patient was referred to cardiothoracic surgery for excisional biopsy. A video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) wedge resection was performed and well tolerated.

Reference

- Manickam R, Mechineni A. Pulmonary Sclerosing Pneumocytoma: An Essential Differential Diagnosis for a Lung Nodule. Cureus. 2022 Jan 10;14(1):e21081.

- Bara A, Adham I, Daaboul O, Aldimirawi F, Darwish B, Haffar L. Sclerosing pneumocytoma in a 1-year-old girl presenting with massive hemoptysis: A case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021 Jan 8;62:49-52.

- Pal P, Chetty R. Multiple sclerosing pneumocytomas: a review. J Clin Pathol. 2020 Sep;73(9):531-534.

- Boland JM, Lee HE, Barr Fritcher EG, Voss JS, Jessen E, Davila JI, Kipp BR, Graham RP, Maleszewski JJ, Yi ES. Molecular Genetic Landscape of Sclerosing Pneumocytomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021 Feb 11;155(3):397-404.

- Boland JM, Lee HE, Barr Fritcher EG, Voss JS, Jessen E, Davila JI, Kipp BR, Graham RP, Maleszewski JJ, Yi ES. Molecular Genetic Landscape of Sclerosing Pneumocytomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021 Feb 11;155(3):397-404.

- Nasr Y, Bettoli M, El Demellawy D, Sekhon H, de Nanassy J. Sclerosing Pneumocytoma of the Lungs Arising in a Child With PTEN Mutation. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2019 Nov-Dec;22(6):579-583.

Not quite.